In this post, I summarize the study of the paper Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System authored by Leslie Lamport published on Communications of the ACM in 1978. The paper dives into the fundamental topics “time and clock” in the distributed system, and proposed several important concepts such as Happened-Before, Logical Clocks, Physical Clocks and State Machine Replication. It is definetely one of the “Must-Read” classic paper in distributed system area.

1. Problem

Before we jump into the discussion, let’s consider the following scenario:

We have two persons A and B. They are having coffee wearing their own watches.

- A read the time by his watch after finishing his coffee, and he said: “I finished my coffee at 13:00”.

- B read the time by his watch after finishing his coffee. and he said: “I finished my coffee at 13:05”.

Suppose they are both honest, can we say that “A finished his coffee before B”?

The answer is no. Since we have no idea whether their watches are “accurate” or not. We can’t have the conclusion of “who finished first”, even though they both announced their reading of the watch honestly. Then what about this:

- A read the time by his watch after finishing his coffee, and he said: “I finished my coffee at 13:00”.

- A made a phone call to B after coffee.

- B answered the call, then finished his coffee and read the time by his watch. He said: “I finished my coffee at 13:05”.

In this scenario, we can have A finished the coffee before the call, and B finished after that. So A’s coffee must be finished before B. This phone call made up a deterministic “happened-before” relationship between two indipendent time system.

By the above example, we know that the common concept/method such as “reading of clock”, “timestamp” can not correctly describe the order of event occurs. However, in the distributed system, this order plays critical role in different algorithims. So, how could we build our “clock” to presisly describe this order? This paper gives us the answer.

2. What is time

The concept of time is fundamental to our way of thinking. It is derived from the more basic concept of the order in which events occur.

For example, if we say some event occurs at 13:00. The critical statements should be: It occurred after we read 13:00 at the clock and before 13:01. By this definition, we know that “time” is a behavior that discrete the continuous-time by the number read on the clock.

3. The definition of distributed system

The so-called distributed system in this paper comprises several spatially separated Nodes. Events in the single node happened sequentially. Different nodes communicate by messaging. We can understand the node as independent computers, processes of operating systems, or different hardware modules in a computer. Especially, we should care about communication latency. It should not be ignored compared to the frequency of events happening in a single node.

4. Happened Before

We define the “happened before” relation on the events in a distributed system, and denote it by “$\rightarrow$”. It satisfied,

- If $a$ and $b$ are the events in the same node, if $a$ comes before $b$, then $a \rightarrow b$.

- If $a$ is the sending of a message by one node and $b$ is the receipt of the same message by another node, then $a \rightarrow b$.

- If $a \rightarrow b$ and $b \rightarrow c$, then $a \rightarrow c$.

If and only if $a \nrightarrow b$ and $b \nrightarrow a$, we say these two events are “concurrent”.

Besides, we define the $\rightarrow$ is a irreflexive relation, which is $a \nrightarrow a$. Obviously, a event which happened before itself does not make any sense.

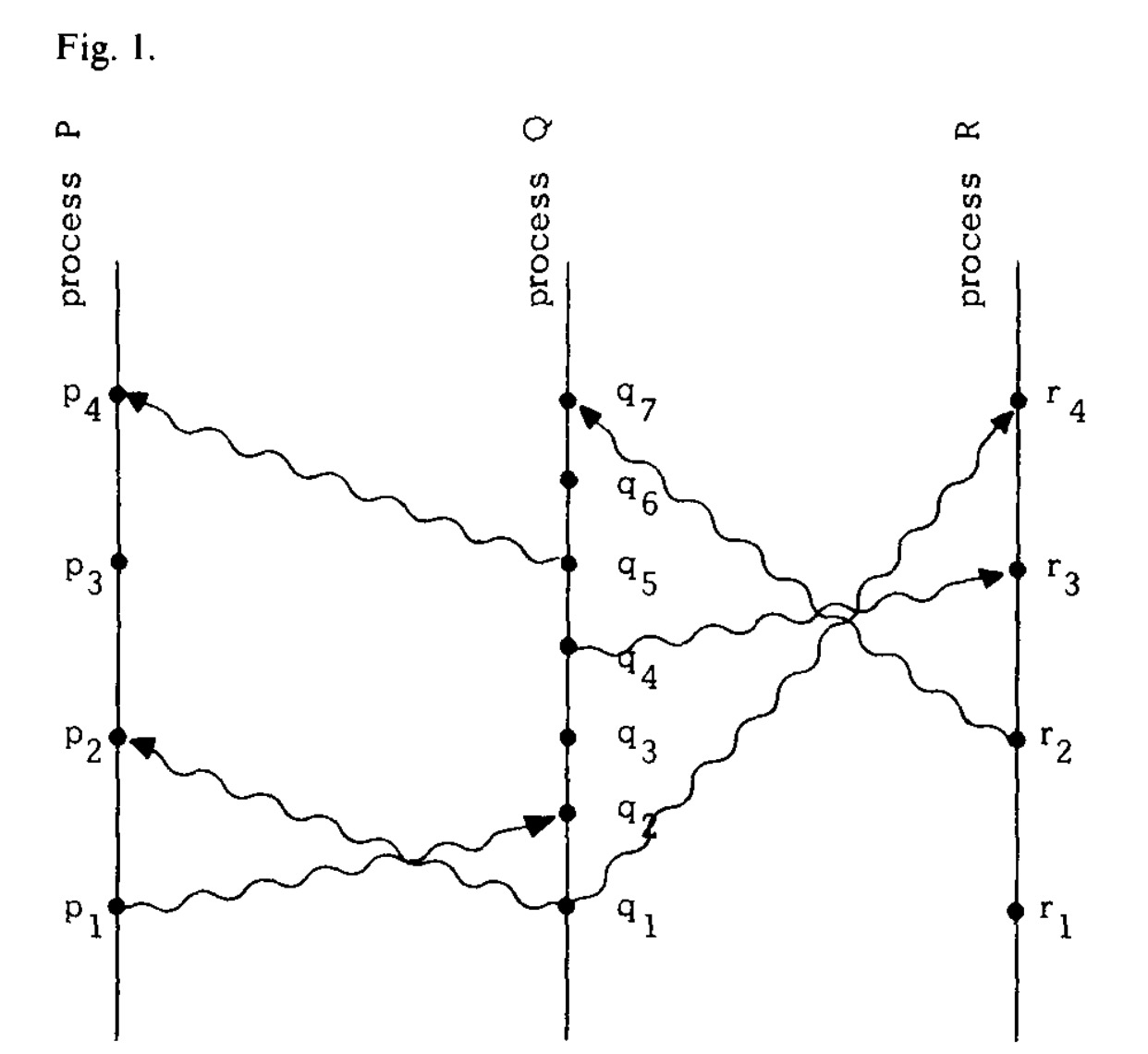

To intuitively describe the relation, Lamport imported the below “space-time Diagram”. In terms of terminology, the “process” in the diagram is the same as the “node” we discussed before. Black dots are the events that occurred on different nodes. The events on a single vertical line(node/process) happened from top to bottom, and the wave arrow between different nodes describes the messaging.

Recall the “happened before” relation. It is not hard to find some satisfying event pairs. Such as $p_1 \rightarrow r_4$, deducted by $ p_1 \rightarrow q_2 \rightarrow q_4 \rightarrow r_3 \rightarrow r_4$.

And there are several concurrent events as well, such as $p_3$ and $q_3$. Even though we can see $p_3$ is above of $q_3$, but for the nodes , they do not aware of this kind of order.

Fig1. space-time diagram

5. Logical Clocks

a clock is just a way of assigning a number to an event.

More precisely, for each node $P_i$, we define clock $C_i$ as a function. It numbers an arbitrary event $a$ of $C_i \langle a \rangle$. For the whole system, denote the happened time of an arbitrary event $b$ as $C \langle b \rangle$. If $b$ happened on node $P_j$, then $ C \langle b \rangle = C_j \langle b \rangle$. Here, the clock $C$ is not the real clock we use in daily life. That is a logical clock simply assign integers to each event to present the order of happening. To follow the “happened before” relation, the clock should satisfied the following Clock Condition.

Clock Condition. For any events $a, b$: if $a \rightarrow b$, then $C \langle a \rangle < C \langle b \rangle$.

C1. If $a$ and $b$ are events in node $P_i$, and $a$ comes before $b$, then $C_i \langle a \rangle < C_i \langle b \rangle$.

C2. If $a$ is the sending of a message by node $P_i$, and $b$ is the receipt of that message by node $P_j$, then $ C_i \langle a \rangle < C_j \langle b \rangle $.

In particular, the the converse proposition of Clock Condition “If $C \langle a \rangle < C \langle b \rangle$, then $a \rightarrow b$” does not necessarily hold.. For example, in Fig1, $(p_2, q_3), (p_3, q_3)$ are concurrent. By $C1$, we have $C \langle p_2 \rangle < C \langle p_3 \rangle$, then we have either $C \langle q_3 \rangle \neq C \langle p_2 \rangle$ or $C \langle q_3 \rangle \neq C \langle p_3 \rangle$, which is confict with concurrent relation.

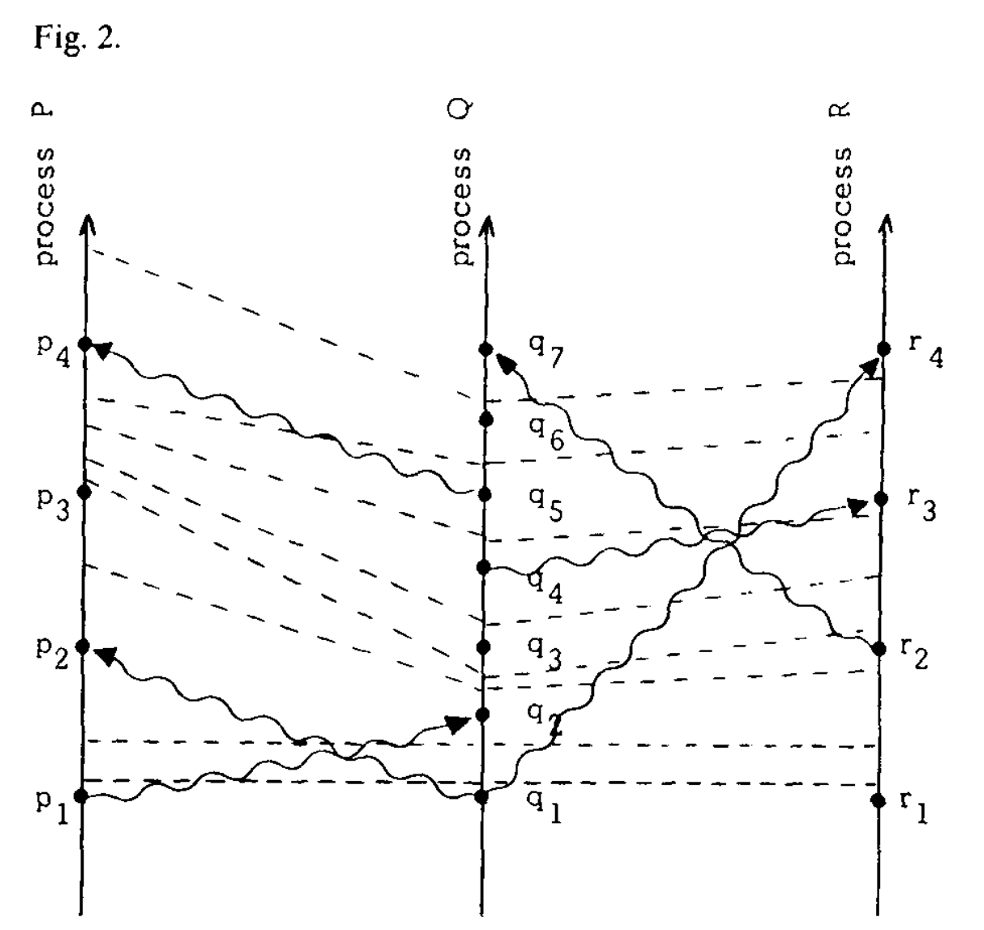

For the logical clock, we can imagine that the “tick” evens keep occurring in a single node. For example, two evens $a, b$ continuous happened in a node $P_i$, and we have $C_i \langle a \rangle = 4, C_i \langle b \rangle = 7$, then we should have three “tick” evens happened between them which numbered $5,6,7$. Therefore, we can add “tick line” to our space-time diagram as Fig.2. By $C1$, we can know that for two evens continuous happened in the same node, there should have at least tick line between them. By $C2$, we can have that every message should go across at least one tick line.

Fig2. space-time diagram with tick line

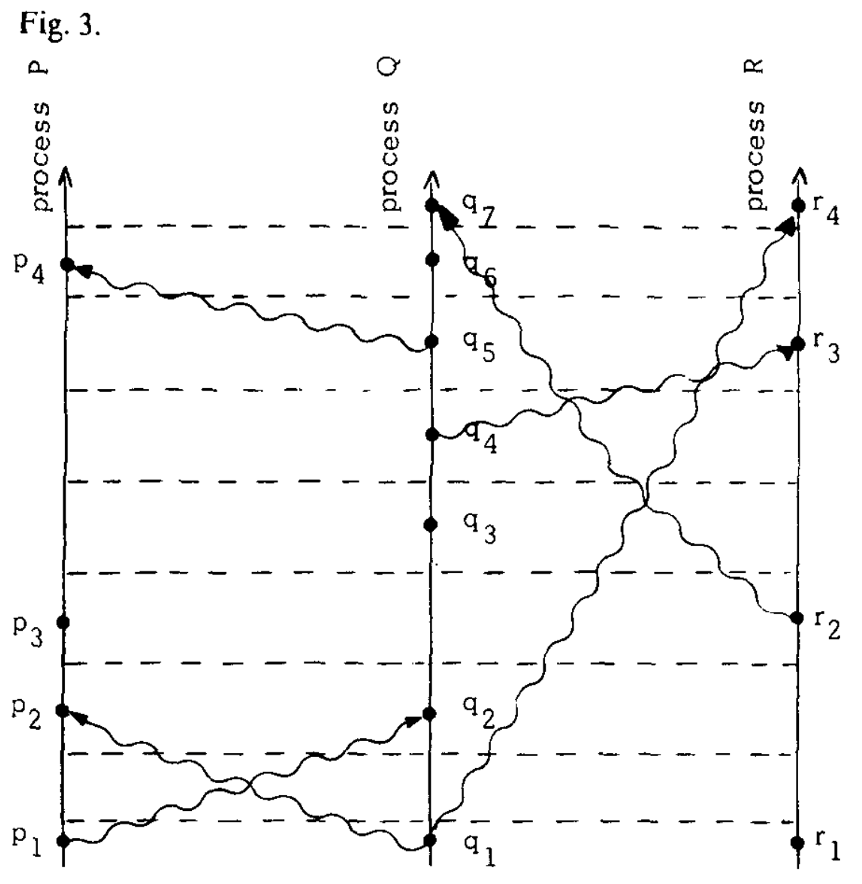

For easy understanding, as Fig3, we can make horizontal the tick line with the same partial order of events and messages.

Fig.3 horizontal the tick line

On a single node $P_i$, our implmentation of logical clock follows(Implementation Rule):

- IR1. $C_i$ increased between any consecutive happened events.

- IR2.

- (a) If event $a$ is the sending of a message $m$, and $m$ contains the timestamp $T_m=C_i \langle a \rangle $. (b)

- (b) When another node $P_j$ receive the message $m$, set $C_j$ as $C_j’$, which $C_j’ >= C_j$ and $C_j’ > Tm$.

6. Total Ordering

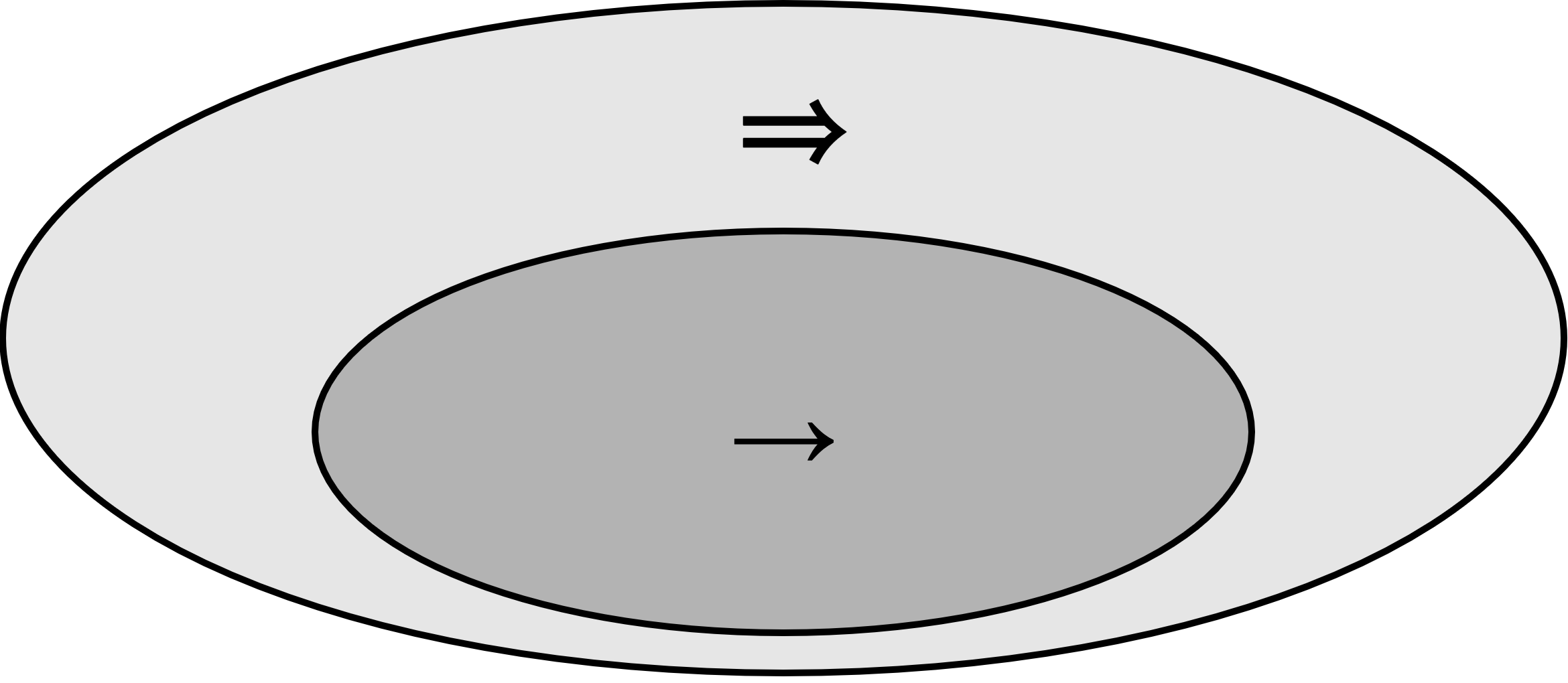

Using the logical clock, we can sort the who events in the distributed system in total order. Firstly, we sort events by logical clocks. For the events have the same logical clock value, we sort them by the pre-defined priority rules $\prec$. e.g. alphabet order.

More precisely, we define the total order $\Rightarrow$. For event $a$ on $P_i$ and $b$ on $P_j$,

we have $ a \Rightarrow b $ if and only if (i) or (ii).

- (i) $C_i \langle a \rangle < C_j \langle b \rangle$.

- (ii) $C_i \langle a \rangle = C_j \langle b \rangle$ and $P_i \prec P_j$.

By the definition of Clock Condition, we can know that if events satisfied $\rightarrow$, then they must satisfied $\Rightarrow$.

Fig4. Total order and partial order

7. Physical Clocks

7.1 Out of the system

To build a physical clock that followed clock condition, we should take care of some “Out of the system” events.

For example, some engineer triggered event $a$ on a node, having a cup of coffee, and triggered event $b$ on another node. The system did’t aware about “coffee”, so we may have $B \Rightarrow A$.

We define the events inside of the system as $\varphi$. Union of events for inside and outside of the system as $\underline{\varphi}$. $\underline{\rightarrow}$ is the happened relation on $\underline{\varphi}$. In the example above, we have $A \underline{\rightarrow} B$, but $A \nrightarrow B$.

Obviously, without the outside infomation, there is no way to have $\underline{\rightarrow}$ only by $\varphi$. Therefore, we have two ways to have $A \rightarrow B$,

- Explicitly importing the ouside information. etc. Event $A$ happened at logical time $T_A$. After taking the phone call, tell the system $T_B$ should greater than $T_A$ explicitly.

- Build a system with the Strong Clock Condition.

Strong Clock Condition. For any events $a, b$ in $\varphi$: if $ a \underline{\rightarrow} b$ then $C \langle a \rangle < C \langle b \rangle$.

Obviously, Strong Clock Condition. is the solution we want. The following describe how to implmente a physical clock that safisfies the Strong Clock Condition.

7.2 Physical Clocks Implimentation

Let $C_i(t)$ be the reading of $C_i$ at physical time $t$. For mathematical convenience, let’s say $C_i$ to be continuously differentiable for $t$, $dC_i(t)/dt$ describe the “speed” of the clock at time $t$.

To make the speed of $C_i$ is close the real time, for all $t$, we must make $dC_i(t)/dt \approx 1$. More precisely, we need to satisfy the following conditions,

PC1. There exists a constant $\kappa \ll 1$ such that for all $i$: $| dC_i(t)/dt - 1 | < \kappa$.

For typical crystal controlled clocks, $\kappa \leq 10^{-6}$.

We also need to keep syncyonize between different clocks, which means for all $i,j,t$, we have $C_i(t) \approx C_j(t)$. So we have,

PC2. For all $i, j$:$|C_i(t) - C_j(t)| < \epsilon$.

Intuitively speaking, the height difference of a single tick line in Fig.2 should not be too large.

Due to the existence of accumulated error, two clock system that run independently will lead to increasing difference. Therefore, we need a way to syncyonize the clock.

首先我们假设我们的时钟满足Clock Condition.,这样我们只需考虑在 $\underline{\varphi}$ 中 $a \nrightarrow b$ 的情况。不难发现,此时 $a$ 与 $b$ 必然发生在不同的节点上。

令 $\mu$ 小于节点间的最小通信时延。即事件 $a$ 发生于物理时间 $t$,事件 $b$ 发生于另一节点,若 $ a\underline{\rightarrow} b$,则 $b$ 最早发生于 $t + \mu$。通常我们可以设定 $\mu$ 为节点间的最小距离除以光速。

为了避免上文中的反常情况,我们必须保证对于任意的 $i, j$ 和 $t$ ,有 $C_i(t + \mu) - C_j(t) > 0$。

结合PC1. 有 $C_i(t + \mu) - C_i(t) > (1- \kappa)\mu$,详细推导见附录8.2。

结合PC2. 有需保证 $ -\epsilon \geq -\mu(1 - k)$,则需有 $\epsilon/(1 - \kappa) \leq \mu$,详细推导见附录8.3。

7.2.1 Physical Clocks Algorithm

下面介绍具体的的算法实现,从而保证上面的公式与PC1,PC2成立。

对于一条发送于物理时间 $t$ ,接收于物理时间 $t’$ 的消息 $m$。我们定义消息的总延迟(total delay) $ v_m = t’ - t$。接受消息的节点当然不知道 $v_m$ 的值,但是它可以知道这条消息的最小延迟(minimum delay) $\mu_m$, $\mu_m \geq 0$ 且 $\mu_m \leq v_m$。我们称 $\xi_m = v_m - \mu_m$ 为不可预测延迟(unpredictable delay)。

对于单个节点上的物理时钟算法的实现,我们有如下的实现规则(Implementation Rule):

- IR1’. 每个节点 $P_i$ 在物理时间 $t$ 没有收到任何消息,那么 $C_i$ 在 $t$ 时刻可微,且 $dC_i(t)/dt > 0$。

- IR2’. (a) 如果 $P_i$ 在物理时间 $t$ 发送消息 $m$ ,那么 $m$ 中包含时间戳 $T_m=C_i(t) $。(b) 当在物理时间 $t’$ 收到消息 $m$ 时,进程 $P_j$ 设置当前时间 $C_j(t’) = max(C_j(t’ - 0), T_m + \mu_m)$。其中$C_j(t’ - 0) = \underset{\delta \rightarrow 0}{ lim }C_j(t’-|\delta|)$。

7.2.1 Physical Clocks Algorithm Proof

现在我们证明上述的实现规则可以确保满足PC2。

将整个系统视为一个有向图,图中的点为各个节点,$P_i$ 到 $P_j$ 的有向边视为其消息链路。

令 $d$ 为有向图的直径(longest shortest path)。$\tau$ 为两个节点之间的最低通信间隔,即任意时间 $t$ 到 $t + \tau$之间,$P_i$ 至少应该发送一条消息给 $P_j$。下面的定理给出系统启动后,至多多久系统会达成满足PC2的时间同步。

定理:假设系统为一个遵循IR1’和IR2’,且直径为 $d$ 的强连通图。对于任意的消息 $m$,$\mu_m \leq \mu$,其中$\mu$ 为某个特定常数,且对于所有 $t \geq t_0$。 (a) PC1 总是成立。 (b) 存在常数 $\tau$ 和 $\xi$,在系统中每条边上,每$\tau$秒会转发一条不可预测延迟最大为 $\xi$ 的消息。则PC2 满足于,对于所有的 $t\gtrapprox t_0 + \tau d$,$\epsilon \approx d(2\kappa\tau + \xi)$,$\mu + \xi \ll \tau$。其证明见于附录8.4。

8.Appendix

8.1 Total Ordering Application: Mutual Exclusion Problem

- 资源必须要在正在访问它的节点释放后,才可以分配给其他节点访问。

- 按节点请求的顺序访问资源,先到先得。

- 如果每个访问资源的节点最终都会释放资源,那么所有请求访问的节点最终都可以成功访问。

8.2 PC1 Proof

由PC1有 $\left | \frac{C_i(t+\mu) - C_i(t)}{\mu} < \kappa \right |$,则有 $(1 - \kappa)\mu < C_i(t+\mu) - C_i(t) < (1 + \kappa)\mu$ 。

8.3 PC2 Proof

继8.2有,$C_i(t) + \mu(1-k) < C_i(t+\mu)$。

故要使得 $C_i(t + \mu) - C_j(t) > 0$,则需有 $C_i(t) - C_j(t) > -\mu(1 - k)$。

由PC2有,$C_i(t) - C_j(t) < -\epsilon$。

故而得,$ \epsilon \leq \mu(1 - k)$。

8.4 定理证明

对于任意的 $i$ 和 $t$,我们定义 $C_i^t$ 为一时钟,在时刻 $t$ 设定为 $C_i$ 并与 $C_i$ 运行速率相同,且永不被修正(reset)。即,

$$ C_i^t = C_i(t) + \int_{t}^{t’}[dC_i(t)/dt]dt \tag{1}$$

对于所有的 $t’ \geq t$,我们注意到由于 $C_i$ 会被修正,有

$$ C_i(t’) \geq C_i^t(t’) \tag{2}$$

假设 $P_1$ 在时刻 $t_1$ 发送消息给 $P_2$,接收于时刻 $t_2$,不可预测延迟 $\leq \xi$,$ t_0 \leq t_1 \leq t_2$。则对于所有的 $t \geq t_2$,我们有

$$ \begin{aligned} & C_2^{t_2}(t) \geq C_2^{t_2}(t_2) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_2) & \qquad [by\ (1)\ and\ PC1] \\ & \geq C_1(t_1) + \mu_m + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_2) & \qquad [by\ IR2’(b)] \\ & = C_1(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - [(t_2 - t_1) - \mu_m] + \kappa(t_2 - t_1) \\ & \geq C_1(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - \xi \end{aligned} $$

因此,利用这些假设,我们可以得到,对于所有的$t \geq t2$,有

$$ C_2^{t_2}(t) \geq C_1(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - \xi \tag{3} $$

现在假设对于 $i =1,…,n$,我们有$ t_i \leq t_i’ < t_{i+1}, t_0 \leq t_1$。在 $t_i’$时,$P_i$ 发送一条消息给 $P_{i+1}$,该消息接收于 $t_{i+1}$,其不可预测延迟小于 $\xi$。反复应用等式(3)可以得到,对于 $t \geq t_{n+1}$,

$$ C_{n+1}^{t_{n+1}}(t) \geq C_1(t_1’) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1’) - n\xi \tag{4} $$

通过 PC1, IR1’, IR2’我们可以推导出,

$$ C_1(t_1’) \geq C_1(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t_1’ - t_1) $$

再结合(4)与(2),我们可以得到对于 $t \geq t_{n+1}$,有

$$ C_{n+1}(t) \geq C_1(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - n\xi \tag{5} $$

对于任意的两个节点 $P$ 和 $P’$,我们能找到一个节点序列 $P = P_0, P_1, …, P_{n+1} = P’, n \leq d$。通过假设 (b),我们能找到时间 $t_i, t_i’$,有 $ t_i’ - t_i \leq \tau $ 且 $ t_{i+1} - t_i’ \leq v $,其中 $v=\mu + \xi$。因此不等式 (5) 成立于对于任何的$t \geq t_1 + d(\tau + v)$, 有$ n \leq d$。对于任意的$i, j, t, t_1$,其中 $ t_1 \geq t_0 $ 且 $ t \geq t_1 + d(\tau + v) $,我们因此有

$$ C_i(t) \geq C_j(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - d\xi \tag{6} $$

令 $m$ 为任意时间戳为 $T_m$ 的消息,其在 $t$ 时刻发送,在 $t’$ 时刻接收。我们假设 $m$ 有一个以一个恒定速率运行的时钟 $C_m$,且有 $C_m(t)=t_m$,$C_m(t’) = t_m + \mu_m$。那么由 $ \mu_m \leq t’ - t $ 可以推导出 $dC_m/dt \leq 1$。规则 IR2’(b)将 $C_j(t’)$ 设置为 $max(C_j(t’ - 0), C_m(t’))$。因此,当时钟被重置时,只可能重置与其他某个时钟相等。

对于任意时间 $t_x \geq t_0 + \mu/(1-\kappa)$,令 $C_x$ 为 $t_x$ 时刻具有最大值的时钟。由于所有的时钟以低于 $1+\kappa$ 的速率运行,我们有对于所有的 $i$ 和所有的 $t \geq t_x$:

$$ C_i(t) \leq C_x(t_x) + (1 + \kappa)(t - t_x) \tag{7} $$

现在我们考虑如下两种情况:(i)$C_x$ 为节点 $P_q$ 的时钟 $C_q$。(ii)$C_x$ 为节点 $P_q$ 在 $t_1$ 时刻发送于消息 $m$ 的时钟。在情况(i)中,(7)简单的成为,

$$ C_i(t) \leq C_q(t_x) + (1 + \kappa)(t - t_x) \tag{8i} $$

在情况(ii)中,由于 $C_m(t_1)=C_q(t_1)$,且 $dC_m/dt \leq 1$,我们有,

$$ C_x(t_x) \leq C_q(t_1) + (t_x - t_1) $$

因此,由(7)有,

$$ C_i(t) \leq C_q(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) \tag{8ii} $$

由于 $t_x \geq t_0 + \mu/(1 - \kappa)$,我们有,

$$ \begin{aligned} & C_q(t_x - \mu/(1 - \kappa)) \leq C_q(t_x) - \mu & \qquad [by\ PC1] \\ & \leq C_m(t_x) - \mu & \qquad [by\ choice \ of \ m] \\ & \leq C_m(t_x) - (t_x - t_1)\mu_m/v_m & \qquad [\mu_m \leq \mu, t_x - t_1 \leq v_m] \\ & = T_m & \qquad [by\ definition \ of \ C_m] \\ & = C_q(t_1) & \qquad [by\ IR2’(a)] \end{aligned} $$

因此,$ C_q(t_x - \mu/(1 - \kappa)) \leq C_q(t_1) $,因此 $ t_x - t_1 \leq \mu(1 - \kappa), t_1 \geq t_0 $。

令 $ t_1 = t_x $,对于情况(i),我们结合(8i)和(8ii)可以推出对于任意的 $t,t_x$,且$t \geq t_x \geq t_0 + \mu/(1 - \kappa)$,存在一个节点 $P_q$ 和一个时间 $t_1$,$t_x - \mu/(1 - \kappa)\leq t_1 \leq t_x$,对于所有的 $ i $,

$$ C_i(t) \leq C_q(t_1) + (1 + \kappa)(t - t_1) \tag{9} $$

若我们选择的 $t$ 和 $t_x$ 满足 $t \geq t_x + d(\tau + v)$,我们可以结合(6)和(9)得到存在一个时间 $t_1$ 和一个节点 $P_q$,对于所有的 $i$,

$$ C_q(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) - d\xi \leq C_i(t) \leq C_q(t_1) + (1 - \kappa)(t - t_1) \tag{10} $$

令 $t = t_x + d(\tau + v)$,我们有,

$$ d(\tau + v) \leq t - t_1 \leq d(\tau + v) + \mu(1 - \kappa) $$

结合(10),我们有,

$$ C_q(t_1) + (t - t_1) - \kappa d(\tau + v) - d\xi \leq C_i(t) \leq C_q(t_1) + (t - t_1) + \kappa[d(\tau + v) + \mu/(1 - \kappa)] \tag{11} $$

结合假设 $\kappa \ll 1$ 以及 $\mu \leq v \ll \tau$,我们可以重写(11)为,

$$ C_q(t_1) + (t - t_1) - d(\kappa\tau + \xi) \lessapprox C_i(t) \lessapprox C_q(t_1) + (t - t_1) + d\kappa\tau \tag{12} $$

由于上式对于所有的 $i$ 成立,我们有,

$$ |C_i(t) - C_j(t)| \lessapprox d(2\kappa\tau + \xi) $$

上式对于所有的 $t \gtrapprox t_0 + d\tau $ 均成立。

证毕。